An operator in the basement assumed a series of valves had been mistakenly left closed.

He did not realise that upstairs a test was being conducted in the nuclear reactor.

The valves were immediately closed, but the damage had been done, triggering a surge of power of about 100 MW, three times what was expected.

In the 108 seconds of extreme heat, various elements in the reactor had been damaged.

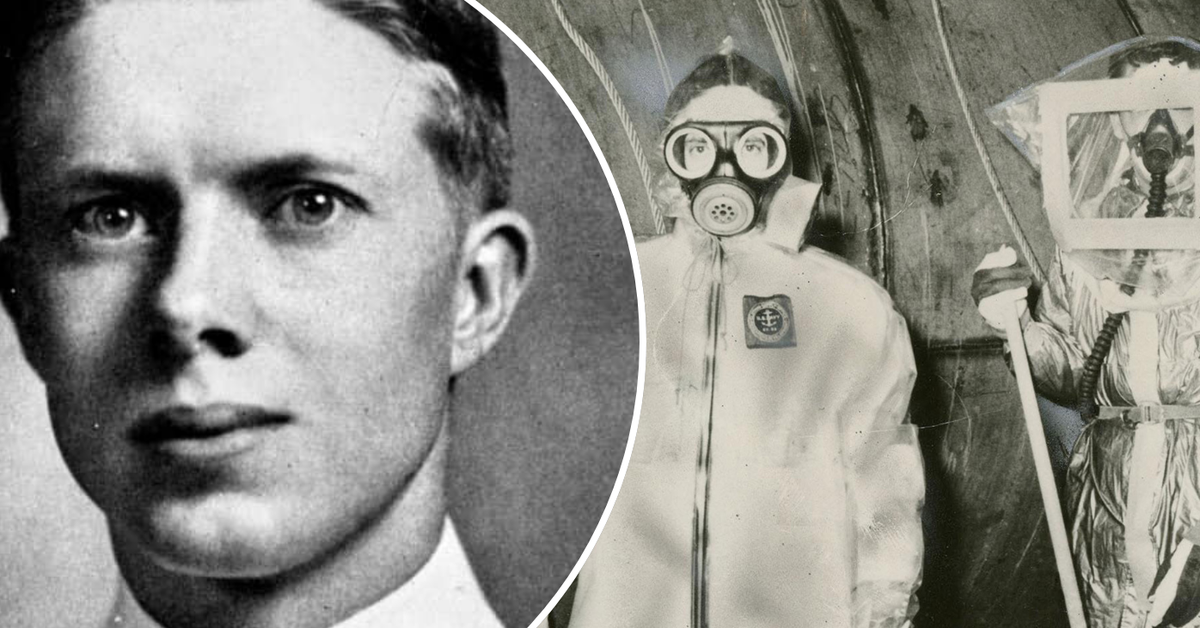

Overwhelmed, the laboratory sent for a US military team to help with the clean-up operation.

Carter had to be lowered into the reactor itself, knowing the exposure to radiation could well be fatal.

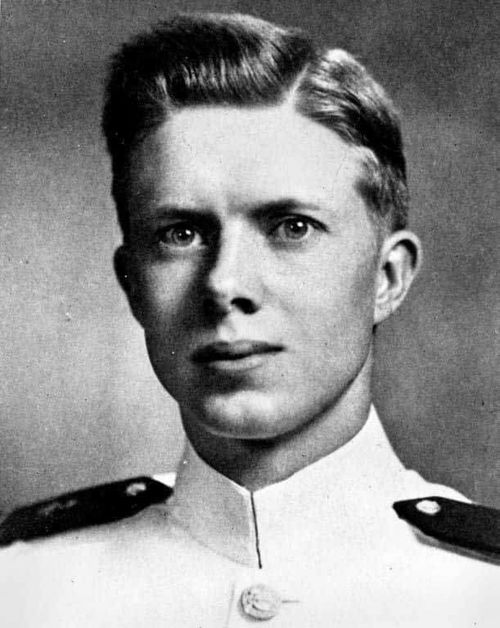

“They let us get probably a thousand times more radiation than they would now,” he said.

“It was in the early stages and they didn’t know.”

Because they wanted to be out of the reactor as quickly as possible, Carter’s team built a replica reactor on a tennis court to practice their operation.

They would only be in the reactor for 90 seconds at a time to limit their exposure.

That would give Carter or other team members enough time to turn one screw.

Carter later remarked he had radioactive urine for six months afterwards.

He was told the exposure would stop him having any children and would shorten his life.

At that point he already had three sons including a newborn. He would have a daughter 15 years later.

The prognosis of a short life because of his radiation exposure turned out to be untrue.